“Polo is perhaps the most ancient of games. All our best games are derived from it, and cricket, golf, hockey and the national Irish game of Hurling are all descendants of polo.”

– Polo historian, Thomas Francis Dale

A sport needs two main elements: instruments and the strategies to be employed in play. To understand TS Dale’s statement, one must seek an explanation as to how Polo affected other modern sports. One needs to see how one of the most ancient sports forged the many games played today.

The ball and the stick bear witness to the first two primordial defence mechanisms that our ancestors must have used. The pelting of stones and striking with wooden sticks of dangerous animals in the wild was then not really a sport or a royal pastime. It was a fierce battle for survival.

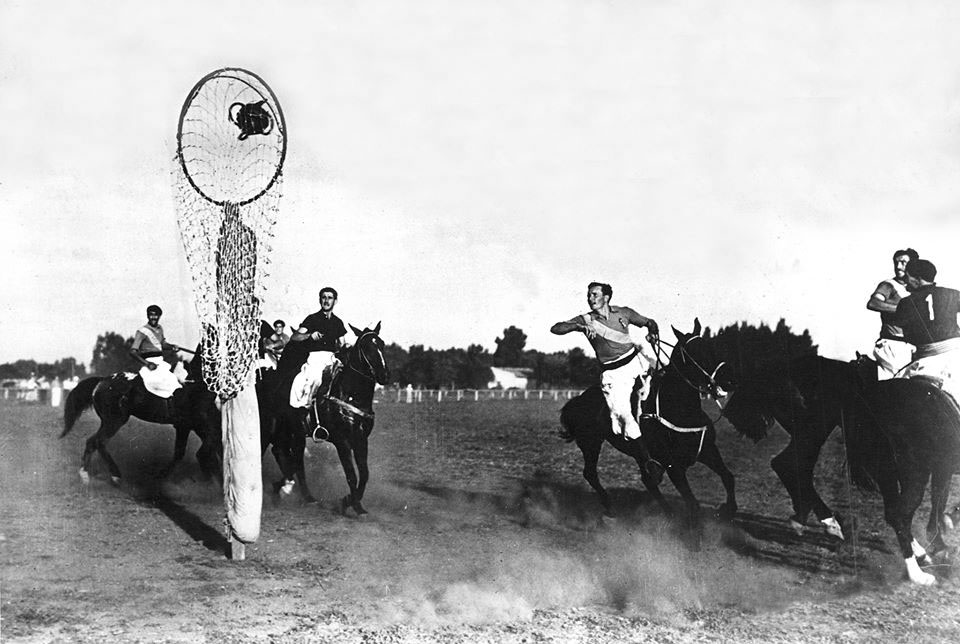

The conditions for battle gradually died down with the establishment of agriculture, but societies still needed trained people to ward off attacks from animals and hunting groups. Hence, sports became a necessity for even the most established and prosperous agricultural societies. The ball games continue to carry the element of force reminiscent of the old spirit for survival. Polo has undoubtedly kept this spirit alive in its most fierce display.

It would still be very late in the archaic past to see the birth of a game remotely recognised as polo; the ball and the stick were certainly etched in a very distant past.

Men used feet for hunting but successfully formed the two instruments that polo would utilise. It was not until the domestication of horses, near present-day Kazakhstan circa 3500 BC, that we can start surmising the birth of the ancient forms of polo.

The development of strategy in games could have given certain dynamics to polo and other subsequent games. The strategy involved the spirit of competition between two players over the fate of the ball. This brings us to a reference to a game played in ancient Egypt. Ann Rosalie David notes in her book ‘Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt’: “A game played by hitting the cat–usually with a wooden peg–into the air with a bat or stick…before landing onto the ground, it would be struck again, and the person who drove the cat farthest would be the winner.”

Surprisingly, the “gulli danda” (tipcats) in India proves to be one of the ancestors of the ball and stick games and could even be said to predate polo.

Polo necessarily adopted this competitive nature, along with the stratagem of stick-and-ball manoeuvring. Buzakashi, played in Afghanistan, continues to use an animal carcass instead of a ball, and instead of hitting it with sticks, holding the carcass in possession determines the winner.

To answer the question as to how stick and ball games acquired teams of opposing interests in play, we must consider the development of hunting and tribal fights. They are of particular interest not only to understand polo but also how that shares close relation to other variety of sports.

Games that dominated sports from the 17th to early 20th century in Europe and South Asia were hunting games, which combined the play of the man and horse. Games like fox-hunting and pig-sticking were immensely popular among the British and were played in their colonies till the 1960s as well. These hunting games explain two important dynamics of the game: team sports and driving the ball to one’s own territory.

Even though hunting was a survival tactic, Europeans from the 17th century onwards took fox hunting as a sport and organised tournaments. The President’s Cup was among the most celebrated fox-hunting events in England. Pig-sticking and polo were often on the same calendar in the sports season, and one could not miss the legendary Sir Pratap, whom Maj Gen Amar Singh Kanota, in his diary, memorises thus: “He had done a lot of pig-sticking, and it was very hard to beat him. Unfortunately, he never competed in any Cup except once for the Jodhpore Cup, which he would most probably have won, but for a disagreement on one point, for which he got angry and went…”

Pig stickers and fox hunters entered polo owing to their masterful skills in manoeuvring the horse, and both these games were equally excellent in training soldiers. Colonel RS Sodhi remarked in an interview with La Polo that he had been in a tournament in the Ganga Doab region for pig-sticking, which, according to him, was parallel in reputation to polo before Independence, and many polo players came from these hunting games.

Games like cricket, golf, football, rugby, hockey, hurling, lacrosse, pato and so on owe, directly or indirectly, their instruments of play and strategies to polo. Those who didn’t possess horses continued to play on feet, employing the same skills they would use on the horse. Games like hurling, pato and lacrosse were developed by the Britishers and taken to South America. Pato became a national game. That is how one understands the statement made by Sir Thomas Francis Dale: “In reality, these games are polo on foot.” This implies that the elements of polo were shared with all games played with a stick and ball.