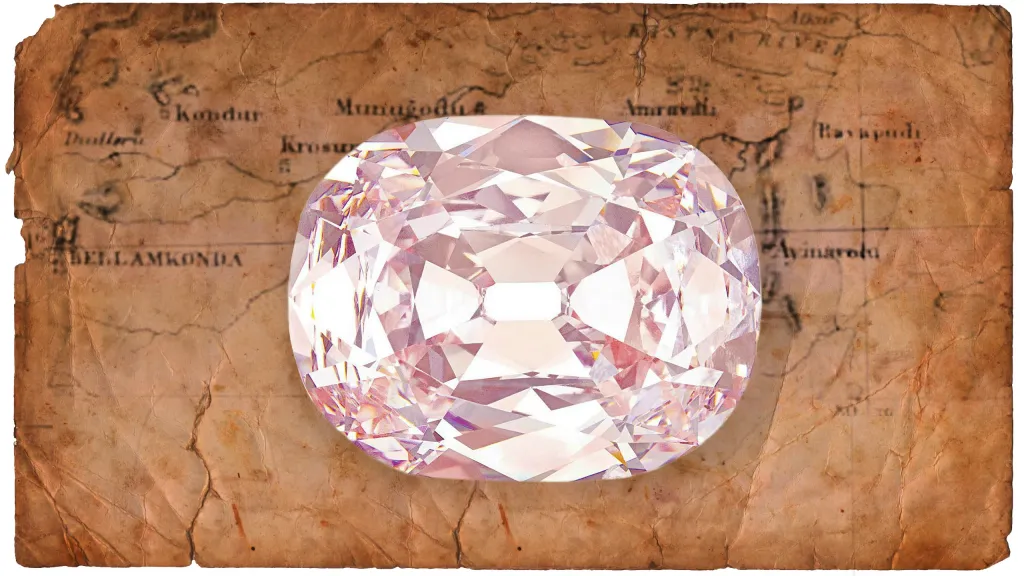

Presiding over the social, political and economic affairs of the Hyderabad State in the south-central Deccan area for over two centuries, the Nizams came to be known for their distinctive Indo-Islamic grandeur. For a long time, the Nizams of India had been associated with unfathomable wealth, which consisted of rare jewels inlaid with precious stones.

The last set of the Hyderbadi Nizami rulers’ wealth was deeply interlinked with their control of the Golconda mines. Osman Ali, the last Nizam of Hyderabad, was thought to be the wealthiest man of his time, the main source of his income being the proceeds from the Golconda mines, the only supplier of diamonds in the world at that time.

Many of the jewels in the Nizam’s household came from these mines. Today, a large portion of Nizam’s jewels is owned by the Government of India, kept in the Reserve Bank of India’s headquarters in Mumbai.

The opulence of the Nizams

The princely state, like several others, rose to power from the crumbling ruins of the Mughal Empire. The founding Nizam of Hyderabad, Mir Qamar-ud-din Khan Siddiqi Bayafandi, was born to parents belonging to two prominent families in the Mughal court. Interestingly, his father, Ghazi Uddin Khan, Qamaruddin Khan, traced his lineage to the First Caliph Abu Bakr, the successor of the Islamic prophet Muhammed.

He and his father were close associates of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, wielding significant influence under the latter’s rule. With the death of Aurangazeb in 1707, the father-son pair lost their previous influence and chose to remain neutral in Aurangzeb’s sons’ war of succession.

Plagued by instability, the Mughal Empire saw two short-lived rules by Auregzeb’s son, Bahadur Shah I and Auregzeb’s grandson, Jalandhar Shah. Neither of these emperors paid much heed to Qamaruddin Khan and Ghazi Uddin Khan. It was their successor, Farrukhsiyar, who took notice of Qamaruddin Khan’s latent leadership traits, entitling him the Nizam-ul-Mulk of Deccan.

However, due to irreconcilable differences, the Mughal emperor withdrew Qamarddin Khan’s status as the administrator of the region. Under the next emperor, Muhammad Shah (1719–48), Qamaruddin Khan found a new lease of life after he was once again entitled the Nizam-ul-Mulk of Deccan by Mohammad Shah.

Administrating in the shadows of the disintegrating empire, Qamaruddin Khan overcame several ordeals, including a rebellion. In 1724, Qamaruddin Khan finally decided to pressurise the then-Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah to declare him the permanent administrator of the Deccan. Freeing himself from the shackles of the Mughal Empire, Qamaruddin Khan established the Nizam rule.

Nizami Hyderabad Turmoil

Over two centuries, the Nizams of Hyderabad bore witness to epochal moments in the socio-political landscape of India: the end of the Mughal Empire, the rise and fall of the Marathas, the rise and fall of the East India Company, the British Indian Empire, and the Partition of India, among others.

With the collapse of British rule and the Independence of India in 1947, political uncertainty spread across the erstwhile British India. Princely states in the country were given the option of ceding to either the Jawarharla Nehru-led Dominion of India or the Muhammed Ali Jinnah-led Dominion of Pakistan. But the Nizam of Hyderabad chose to join neither.

Despite protestations, the Nizam declared his Nizami Hyderabad province as an independent state as the third Dominion, attempting to become an independent monarchy in the British Commonwealth. The Government of India sent out diplomatic envoys to negotiate a peaceful ascension of the territory to India. But the Nizam rebuffed the attempts. He was eventually forced to abdicate after the Indian military launched an armed operation.

Now, having been dethroned, rumours swirled across the streets of Hyderabad that the former monarch would quickly proceed to shift his wealth, mostly jewels, outside of India to keep them out of the government’s reach. But the Nizam denied it in a letter, noting: “If I were to remove my wealth and jewellery outside India, I would have done it before the partition of India.”

Though much of his landed property, known as Sirf-e-khas, was placed under the government’s administration, the Nizam and his family were permitted to retain some of their landed property and almost all of their jewels. But the government wanted him to direct his treasurers to prepare an inventory of the jewels.

According to an account in the Deccan Chronicle: “The inventory included 30 sets of jewellery contained in trays; closed boxes of jewellery sets in the name of his eldest wife Dulhan Pasha and 7 other ‘ladies of senior position residing in the Palace’; 5 gold bricks; 6 gold bars; 65 gold chips; one large gold brick; 80,000 Ashrafis in HEH Treasury; 100,000 Ashrafis and 10,000 Sovereigns in the Nazari Bagh Treasury; 8 crore pieces of Hali Sicca Rupee coins (pure silver); and 7 crore Hali Rupee currency notes.

” Mir Osman Ali shifted them into numerous trusts he’d created, with explicit conditions stating these could not be touched until after his and his son, Azam Jah’s death. These eventually came under the administration of the Indian government.

Jewels in Nizam’s Collection

The Nizam held a priceless assortment of jewels. We present an account of a few of them:

Necklaces: The Nizams possessed a number of invaluable necklaces. Inspired by Indo-European artistic elements, they imbibed all manner of gemstones. However, amongst the most notable pieces are those with Pachchikam craftsmanship. Pachchikam necklaces have delicate, dainty characteristics with intricate gemstone work. The Pachchikam variant traces its roots to Gujarat, where it came to be inspired by jewels previously worn by sixteenth-century European nobility. In later centuries, it came to represent a fusion of both these cultures, Indian and European.

Earrings: Crafted in vibrant hues of reds and greens, these were called Karn phool. The earrings reflected Indian craftsmanship, mostly from the Deccan.

Armbands: Though often worn by men, they later came to be worn by women too. The most notable ones worn by women were crafted in the Jaipur-origin Kundan variety. Kundan work involves elaborate stonework embellishments, inlaid with single un-cut diamonds and other semi-precious stones.

Waistband belts: According to an account, “Post the rapid fall of the Mughal empire, the Nizams quickly came to adopt a more westernised taste in their outfits. The high-collared coats, popular with the Europeans, meant the Nizam could no longer show off his exquisite neck pieces. As a result, he wore adornments like waistband belts, which became an indispensable part of the Nizams’ jewellery collection.” These belts were inlaid with a variety of precious and semi-precious stones.

Anklets: These were worn by women, often a symbol of their marital status. They were gifted to the bride by the groom as a symbol of his wish to take her as his wife. These, like the other assortment of jewels, were similarly adorned with precious gemstones in accordance with a woman’s status in the court.